The New Latvian Red Data Book is the most comprehensive and up-to-date scientific compilation of recent decades on rare, threatened, and extinct species in Latvia. It provides the public, policy-makers, and nature conservation stakeholders with an overview of the conservation status of these species in Latvia and supports efforts to ensure their long-term protection.

The electronic version of the book is freely available to all interested readers. The publication is structured into six thematic volumes and can be downloaded in PDF format (in Latvian) via the links below:

The new edition of the Latvian Red Data Book comprises six volumes and includes descriptions of 1,069 taxa (including species, subspecies, populations, and others). It covers not only rare, threatened, and extinct species in Latvia, but also species that are classified as Near Threatened or for which insufficient data are available to assess extinction risk.

The Latvian Red Data Book was prepared within the LIFE Programme project “Threatened Species in Latvia: Improved Knowledge and Capacity, Information Flow and Awareness” (LIFE FOR SPECIES). The project is implemented by the Institute of Biology of the Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Latvia, in cooperation with the Nature Conservation Agency, Daugavpils University, and the Latvian Ornithological Society, with financial support from the European Commission’s LIFE Programme and the Ministry of Smart Administration and Regional Development.

Photo: Olīvija Z.S, NCA

On 22 January, the new edition of the Latvian Red data book was officially launched at the University of Latvia. It represents the most comprehensive and up-to-date scientific compilation of rare, threatened, and extinct species in Latvia produced in recent decades. The publication provides the public, policy-makers, and nature conservation professionals with an authoritative overview of the conservation status of these species in Latvia and supports efforts to ensure their long-term protection.

The new edition of the Latvian Red data book comprises six volumes and includes descriptions of 1,069 taxa (including subspecies, populations, and other units). In addition to rare, threatened, and extinct species, it also covers species classified as near threatened as well as species for which available data are insufficient to assess extinction risk.

“After more than 20 years, we once again have a scientifically robust and internationally comparable assessment of the most vulnerable components of Latvia’s natural heritage. This publication is not only a benchmark of our capacity to safeguard biodiversity, but also an important tool for strengthening public knowledge and understanding of natural values. It is not merely a data repository, but a national-level symbol and a modern instrument that will support informed decision-making in nature conservation for decades to come,”

emphasises Laura Anteina, Director General of the Nature Conservation Agency (NCA).

The content of the book was developed over a four-year period (2021–2025), bringing together a broad range of scientists and nature experts. For the first time in Latvia’s history, species threat and extinction risk assessments were carried out in accordance with the globally recognised methodology of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), ensuring international comparability and wider applicability of the results.

“We hope that the new Red data book will become a valuable source of information for everyone who cares about Latvia’s nature—researchers, students, school pupils, and nature enthusiasts alike. It will help identify which species require our immediate attention,”

notes Gunta Čekstere-Muižniece, project manager of the LIFE FOR SPECIES project.

The publication is structured into six thematic volumes: fungi, lichens and slime moulds; mosses and stoneworts; vascular plants; invertebrates; fishes, amphibians, reptiles and mammals; and birds.

More than 55 species experts from Latvia and Estonia contributed to the assessments, which were peer-reviewed by 37 international experts from eight European countries. Both expert workshops and public discussions were organised, allowing broader societal engagement in the process.

The electronic version of the Latvian Red data book will soon be freely available to the public at https://sarkanagramata.lu.lv/. The printed edition has been available for consultation since 23 January at the nature centres of Rāzna, Ķemeri and Gauja National Parks, the North Vidzeme Biosphere Reserve, as well as at the National Library of Latvia. Thanks to cooperation with the National Library of Latvia, the books will also become available in major public and educational libraries across the country in the coming months.

The Latvian Red data book was prepared within the LIFE Programme project “Threatened Species in Latvia: Improved Knowledge and Capacity, Information Flow and Awareness” (LIFE FOR SPECIES). The project is implemented by the Institute of Biology of the Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Latvia, in cooperation with the NCA, Daugavpils University, and the Latvian Ornithological Society, with financial support from the European Commission’s LIFE Programme and the Ministry of Smart Administration and Regional Development.

This publication reflects only the views of the LIFE FOR SPECIES project and cannot be considered an official position of the European Union. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained here.

Closing out the year, our featured species of the month for November and December is green shield moss (Buxbaumia viridis).

Green shield moss is a small and elusive species that serves as an indicator of old-growth and natural forest habitats.

It is one of the few moss species protected at the European level and is listed under the Bern Convention and the EU Habitats Directive. In Latvia, the species is strictly protected, and micro-reserves may be established to safeguard its habitats. Forests where the species occurs must be preserved, along with its suitable substrate – dead conifer wood. Continued monitoring is needed to study long-term population trends.

Learn more about the species in the fact sheet. A PDF version is available here.

The species is threatened by logging in suitable forests and by the removal of dead wood. Drainage and land improvement near known sites can also negatively affect the moss by altering the forest microclimate. In Latvia, green shield moss is assessed as Vulnerable (VU) due to its very small population, while at the European scale it is considered Least Concern (LC).

On 4th of December, the Ministry of Smart Administration and Regional Development hosted the “LIFE Award 2025” ceremony, honoring Latvia’s most outstanding LIFE projects in the fields of nature, environment, and climate. The University of Latvia’s LIFE FOR SPECIES project received the award in the category “Most Significant LIFE Contribution to Environmental Protection”.

This was the third “LIFE Award 2025” ceremony. Its aim is to promote awareness of the European Commission’s LIFE Programme in Latvia by identifying and showcasing the most successful projects financed through LIFE calls and implemented by Latvian institutions.

During the awards ceremony, the most impactful Latvian LIFE projects were recognised across nine categories for their important contributions to nature conservation, climate action, and the environment, helping to build a greener and more sustainable Latvia. The ceremony took place at the Environmental Education Centre “Botania” of the National Botanical Garden and brought together nearly 100 attendees.

The LIFE FOR SPECIES project team extends sincere appreciation to the jury, the organisers, and everyone who has contributed to achieving the project’s goals. Warm congratulations also go to all nominees and LIFE projects in Latvia for their dedicated work towards our shared nature, environment, and climate objectives.

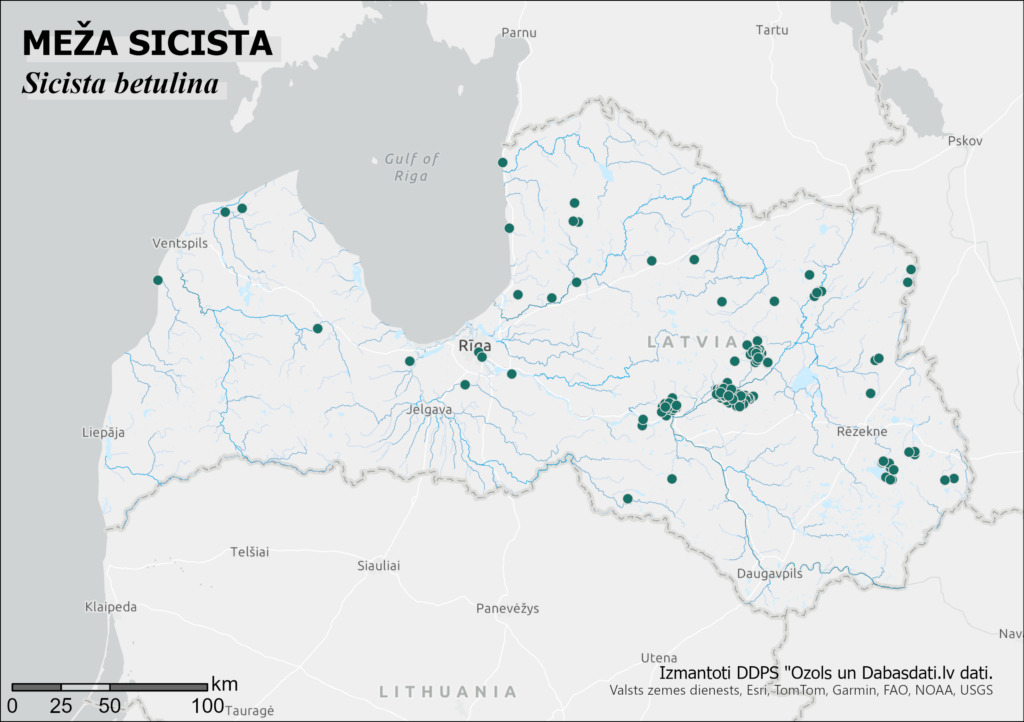

In this golden autumn month, one of Latvia’s smallest rodent species – the northern birch mouse – prepares to enter hibernation.

This species is active at dusk and during the night. Before hibernation it feeds intensively, and can occasionally be spotted during daylight hours. Compared with other rodents of similar size, the northern birch mouse is relatively calm and may not flee immediately from humans unless sudden movements are made.

You can read more about the species and how you can help protect it in its fact sheet (PDF version available here). Fact sheet design: Kristīna Bondare.

Within the project, the northern birch mouse has been assessed as Least Concern (LC) and therefore will not be included in the new Red Book.

On 25–26 September 2025, the international conference of the Nature Conservation Agency’s LatViaNature project – “Together for Nature Conservation: Public and Private Sector Involvement” – took place at the University of Latvia House of Nature in Riga. The event gathered 150 nature conservation experts and professionals from 16 European countries.

The conference provided insights into the latest European Commission developments in nature protection and the practical implementation of the new EU Nature Restoration Law. Participants also explored innovative approaches, shared experience, and best practice examples from across Europe that contribute to achieving the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 targets. The event brought together policymakers, experts and practitioners, NGOs, and other stakeholders. The working language of the conference was English.

The LIFE FOR SPECIES project team also participated, presenting a poster on communication tools applied in the project: “Public engagement in practice: lessons from the LIFE FOR SPECIES project”.

More information and full recordings of the conference are available here:

https://latvianature.daba.gov.lv/en/conference-2025/

Sincere thanks to the organisers for delivering a high quality conference.

A heartfelt thank you to Jelgava Technology Secondary School for organizing the excellent event “One Step Closer” for students of grades 10–12 from the Zemgale region, held on 24 September 2025. The event brought together more than 150 students from five regional schools.

Project manager Gunta Čekstere-Muižniece giving a presentation. Photo: Edgars Krinbergs

The aim of the event was to support students in choosing topics for their research or creative projects and to inspire collaboration with specialists from different fields.

The field of biology and the LIFE FOR SPECIES project were represented by project manager Gunta Čekstere-Muižniece (University of Latvia, Institute of Biology), who introduced participants to the latest research directions in biology, the upcoming new edition of the Latvian Red Data Book, and later provided individual consultations to students at the project stand.

We are delighted that so many young people showed interest in research across various subfields of biology, as well as in rare, endangered, and protected species!

Did you know that protected fungi can also be found in meadows, not just in forests? This month, we highlight the crimson waxcap (Hygrocybe punicea), one of the most striking grassland fungi in Latvia.

Although in some countries the crimson waxcap is considered edible, it is not recommended to eat this mushroom, as it accumulates cadmium, which can be toxic and cause digestive disturbances. Of course, the species should also be protected due to its rarity.

The crimson waxcap is a grassland fungus with an important ecological role – it acts as a soil saprotroph, forms symbiosis with mosses, or sometimes mycorrhiza with trees growing in meadows. It also has high aesthetic value, as its colorful fruiting bodies decorate the grasslands in autumn.

You can read more about the species and how you can help protect it in its fact sheet (PDF version available here). Fact sheet design: Kristīna Bondare.

The body of the crimson waxcap reaches up to 15 cm in height. The cap is 5–12 cm wide, vermilion to blood-red, shiny, sticky, bell-shaped, with an uneven and often cracked edge. The flesh is white and has a faint smell. The gills are yellow to orange-red, spaced apart, and attached to the stem. The stem is 6–12 cm long and 0.8–2.0 cm thick, red-yellow to red, white at the base, cylindrical, glossy, and not sticky.

In Latvia, the crimson waxcap is classified as a Critically Endangered (CR) species.

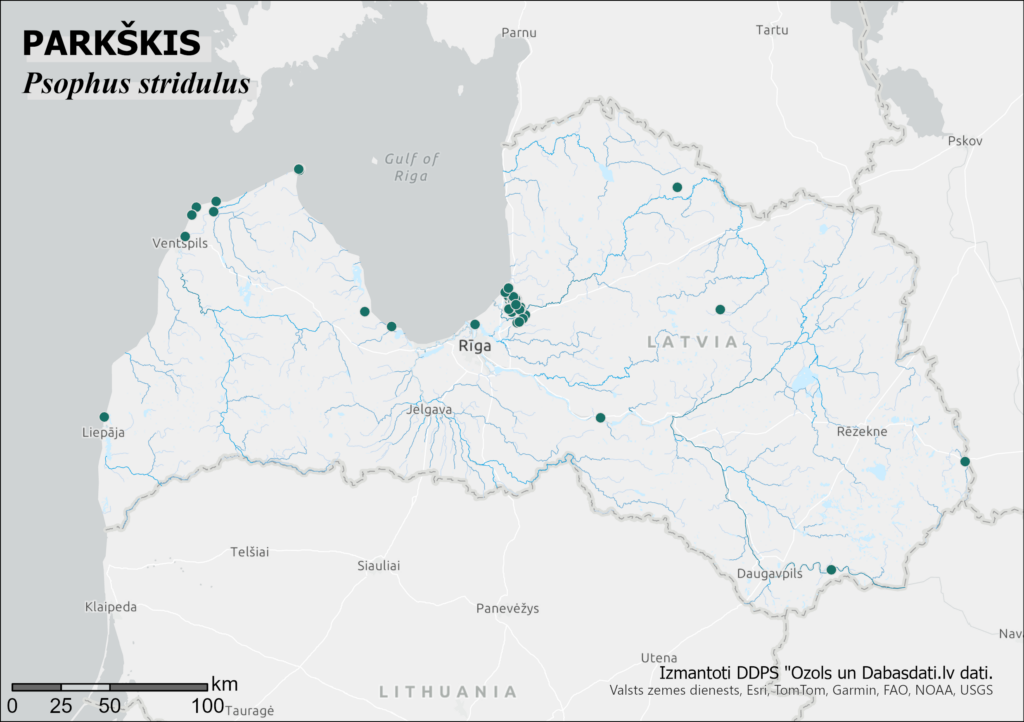

This month, we highlight the rattle grasshopper (Psophus stridulus) - a small grasshopper species that can be observed in nature from mid-July until the end of September.

The Latvian name of the species derives from the characteristic rattling sound produced by males during flight. Because of its bright red hindwings, the species is also known as the red-winged grasshopper.

Adult individuals can be seen from mid-July to late September. They are well camouflaged in their surroundings, so most often the species is detected by spotting or hearing flying males.

You can read more about the species and how to help protect it in its fact sheet (PDF version available here). Fact sheet design: Kristīna Bondare.

The rattle grasshopper is a small, robust grasshopper with a dark grey (sometimes brown) and mottled coloration. Its hind legs feature light stripes, and the pronotum (thoracic shield) is arched upward with noticeable depressions on both sides. The hindwings are orange-red with black tips.

Females are larger and stockier than males, and their wings usually do not extend beyond the tip of the abdomen.

Distribution map author: Jānis Ukass

In Latvia, the rattle grasshopper is classified as an Endangered (EN) species.

On 26 July 2025, the Meadow Festival took place in Dreiliņkalns Park, organized by the Latvian Fund for Nature. This all-day event was dedicated to natural meadows and nature-friendly practices.

Throughout the day, the LIFE FOR SPECIES project team informed festival visitors about the upcoming Latvian Red Data Book, protected species, and hosted a quiz as well as an activity corner for the youngest participants.

The quiz created for the festival is still available — everyone is welcome to test their knowledge here:

👉 https://forms.cloud.microsoft/e/8ty7WEjFnb

For the youngest visitors, we offered creative activities, including mask making, puzzle assembling, and fun worksheets.

A heartfelt thank you to everyone who visited the LIFE FOR SPECIES tent, and to the festival organizers for putting together such a wonderfully arranged event!