As the LIFE FOR SPECIES project nears its conclusion, the team is increasingly engaged in sharing experiences and results with others—helping to ensure the long-term impact and transferability of the project’s outcomes.

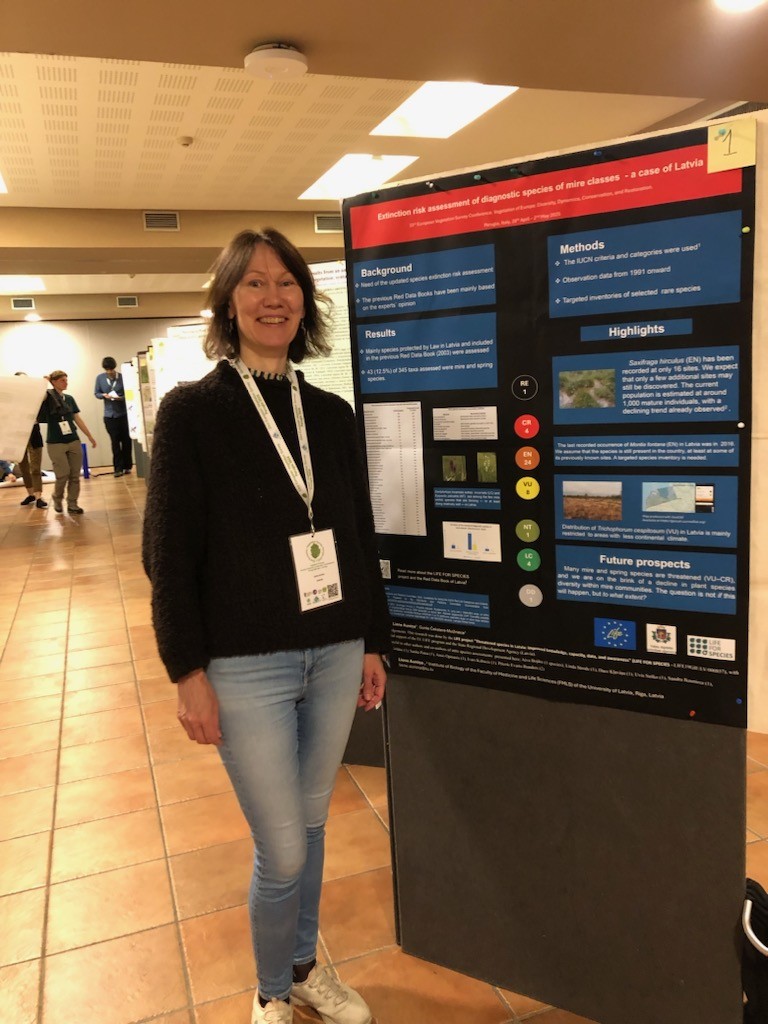

From April 28 to May 2, 2025, Liene Auniņa, head of the vascular plant species group from the LIFE FOR SPECIES team at the University of Latvia’s Institute of Biology, participated in the international conference “33rd European Vegetation Survey – Vegetation of Europe: Diversity, Dynamics, Conservation, and Restoration” in Perugia, Italy. She presented a poster titled “Extinction risk assessment of diagnostic species of mire classes – a case of Latvia,” showcasing the IUCN-based assessment results for 41 mire and spring species in Latvia. These included both specially protected species and those listed in the 2003 edition of the Latvian Red Data Book.

On May 8, project coordinator Jēkabs Dzenis presented the project’s activities to partners of the LIFE urbanCircles project from Latvia, Estonia, and Denmark. The presentation focused particularly on the conservation of endangered species in urban environments.

On May 15, the project’s cartographer Jānis Ukass gave a presentation at the Latvian Esri Software Users Conference, discussing the challenges and solutions in spatial data processing for the development of the Latvian Red Data Book.

On May 21, the LIFE FOR SPECIES team participated in a working meeting with Latvian and Lithuanian partners of the LIFE OsmoBaltic project. Jēkabs Dzenis introduced the project’s key activities, especially the work on updating the protected species list. The meeting also included in-depth discussions on the technical solutions developed for entering, processing, and visualizing species spatial data within the Ozols Nature Data Management System.

On June 2–3, the project team helped host a visit from Danish nature conservation experts to Latvia. Project expert Dāvis Ozoliņš presented the project's extinction risk assessments, with a particular focus on freshwater-associated invertebrates. Meanwhile, Jēkabs Dzenis led an educational hike through Gauja National Park, showcasing its natural values and the broader species protection challenges in Latvia.

Special thanks to Baltic Environmental Forum, LIFE GoodWater IP, Latvian LIFE Help Desk, and the LIFE IP LatViaNature project team for their collaboration in organizing this successful visit!

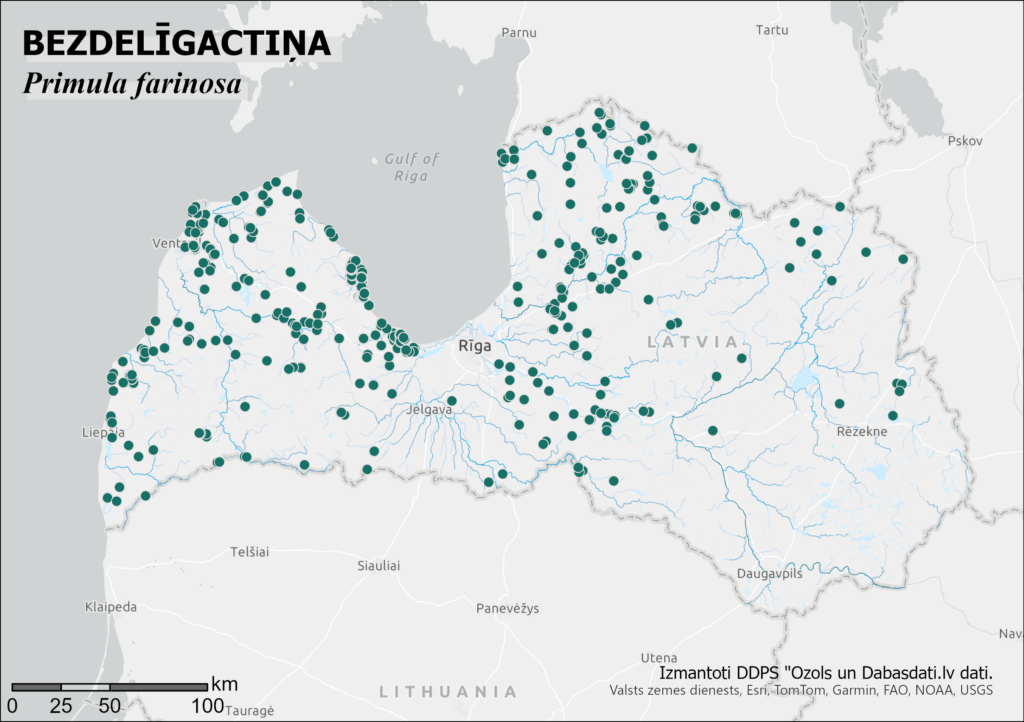

This weekend, many of us will be heading out into nature in search of traditional midsummer plants. But before the celebrations begin, we encourage you to get acquainted with this month’s protected species – the bird’s-eye primrose (Primula farinosa). Learn how to recognize it, so it doesn’t accidentally end up in a festive wreath or decoration!

The species name refers to the bright yellow ring of stamens at the center of the flower. In Latvian folk tradition, the plant is also known by several other names, such as asariņas, bezdelīgactiņš, gaidelīte, gaigaliņi, and putnactiņa. The scientific name “farinosa” comes from the mealy coating on the underside of the leaves and the flower stalk, giving it a powdery appearance.

The bird’s-eye primrose is a perennial herbaceous plant that grows up to 25 cm tall. Its flowers are pinkish-purple and arranged in dense clusters on multiple flower stalks. The leaves form a rosette and have a white, mealy underside, as do the flower stalks. In the right conditions, the plant can live for up to 20 years!

You can read more about the bird’s-eye primrose and how you can help protect it in the species fact sheet (available in latvian). The PDF version is available [here]. Fact sheet design by Kristīna Bondare.

The species is threatened by the drainage of fen meadows and grasslands, as well as the abandonment of mowing or grazing. These impacts are worsened by climate change, prolonged droughts, and drainage in surrounding areas. Additional threats include afforestation and ploughing of its habitats.

In the LIFE FOR SPECIES project, the bird’s-eye primrose has been assessed as Vulnerable (VU) due to its small, fragmented, and declining range, alongside observed loss of habitat area and quality.

Work continues on developing proposals for updating Latvia’s list of protected species. On June 4, a stakeholder meeting took place in Ķemeri National Park, bringing together representatives from state institutions, the commercial sector, research bodies, and NGOs. The aim was to share progress so far, present conclusions from the ongoing legal review, and gather input on next steps for the project’s implementation.

The second part of the meeting took place outdoors, in the habitats of threatened species, where participants discussed the challenges and possible solutions for species conservation directly in the field.

Key topics addressed during the meeting included:

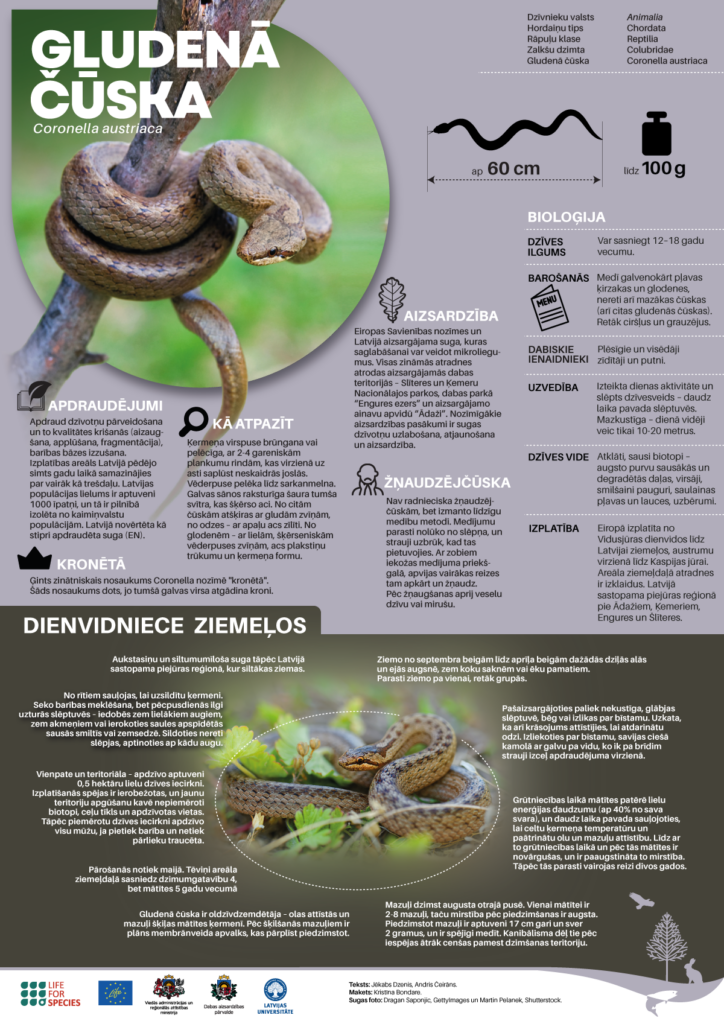

As May draws to a close, the weather finally begins to treat us to warmer days, inviting more frequent outings into nature. During your walks, keep an eye out for this month’s protected species – the smooth snake (Coronella austriaca).

The genus name Coronella comes from the dark markings on the top of the head, which faintly resemble a crown. The smooth snake’s body can be brownish or greyish, with 2–4 longitudinal rows of spots that merge into diffuse bands toward the tail. The underside is grey to reddish-black. A narrow dark stripe runs along the side of the head, passing through the eye. It differs from other snakes by having smooth scales; from the common viper (adder) by its round pupil; and from slow worms by its large, transverse belly scales, lack of eyelids, and more defined body shape.

The smooth snake is cold-blooded and thermophilic, meaning it thrives in warmth. In Latvia, it is found mainly in coastal regions, where winters are milder.

Although snakes may not be everyone's favorite encounter, the smooth snake is non-venomous, and spotting one in the wild is truly a rare event. In the LIFE FOR SPECIES project, it is assessed as Endangered (EN), meaning it faces a very high risk of extinction in the wild.

Smooth snakes mate in May, making this the time when they are most likely to be seen. During pregnancy, females expend a significant amount of energy – up to 40% of their body weight – and spend a lot of time basking to raise their body temperature and speed up the development of eggs and young. As a result, females become weakened during and after pregnancy, with increased mortality rates. For this reason, they usually reproduce only once every two years.

The smooth snake is ovoviviparous – the eggs develop and hatch inside the female’s body. At birth, the hatchlings are encased in a thin membrane that breaks open during birth.

Young snakes are born in the second half of August. A female typically gives birth to 2–8 hatchlings, but postnatal mortality is high. At birth, they are around 17 cm long, weigh about 2 grams, and are capable of hunting. Due to cannibalism, they try to leave their birthplace as quickly as possible.

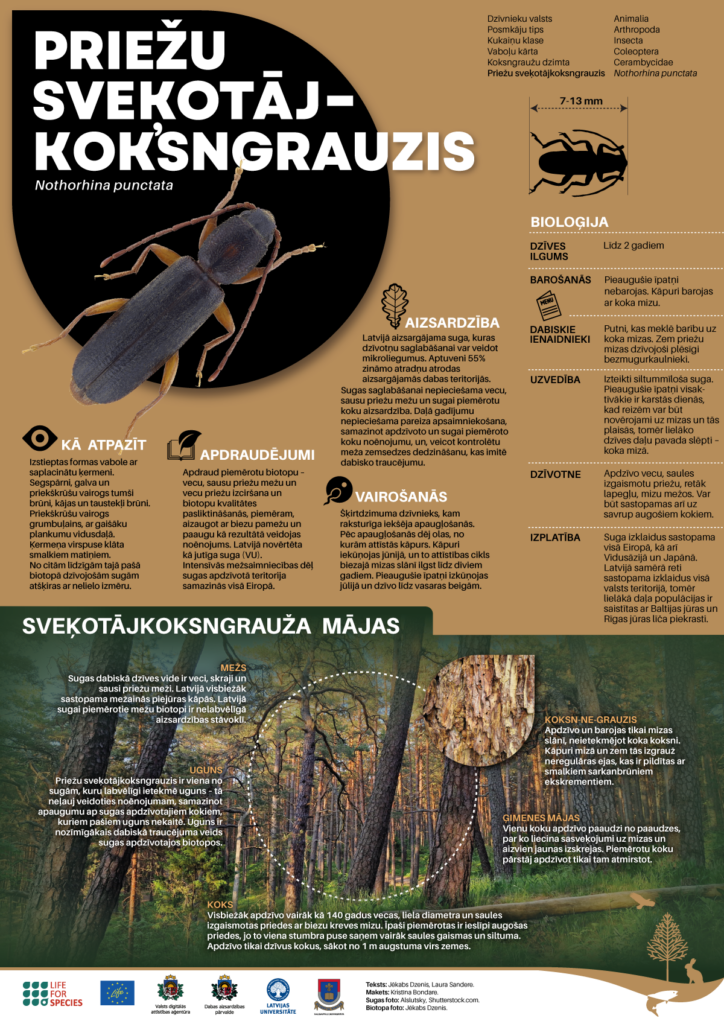

This April, we are highlighting a species with a real tongue-twister of a Latvian name – priežu sveķotājkoksngrauzis (Nothorhina muricata).

The beetle has an elongated and flattened body shape. The elytra, head, and pronotum are dark brown, while the legs and antennae are brown. The pronotum is rough-textured with a lighter patch in the center. The body surface is covered with fine hairs. It can be distinguished from other similar species living in the same habitat by its relatively small size.

Interesting fact: The beetle is one of the species positively affected by fire – fire prevents excessive shading by reducing undergrowth around the beetle's host trees, which are themselves resistant to fire. Fire is the most important natural disturbance factor in the beetle’s habitats.

Map by Jānis Ukass

In Latvia, the species is threatened by the loss of suitable habitat – specifically, the logging of old, dry pine forests and the decline in habitat quality caused by overgrowth of dense underbrush and young trees, which leads to increased shading. The species has been assessed as Vulnerable (VU) in the project. Unfortunately, due to intensive forestry practices, its range is declining across Europe.

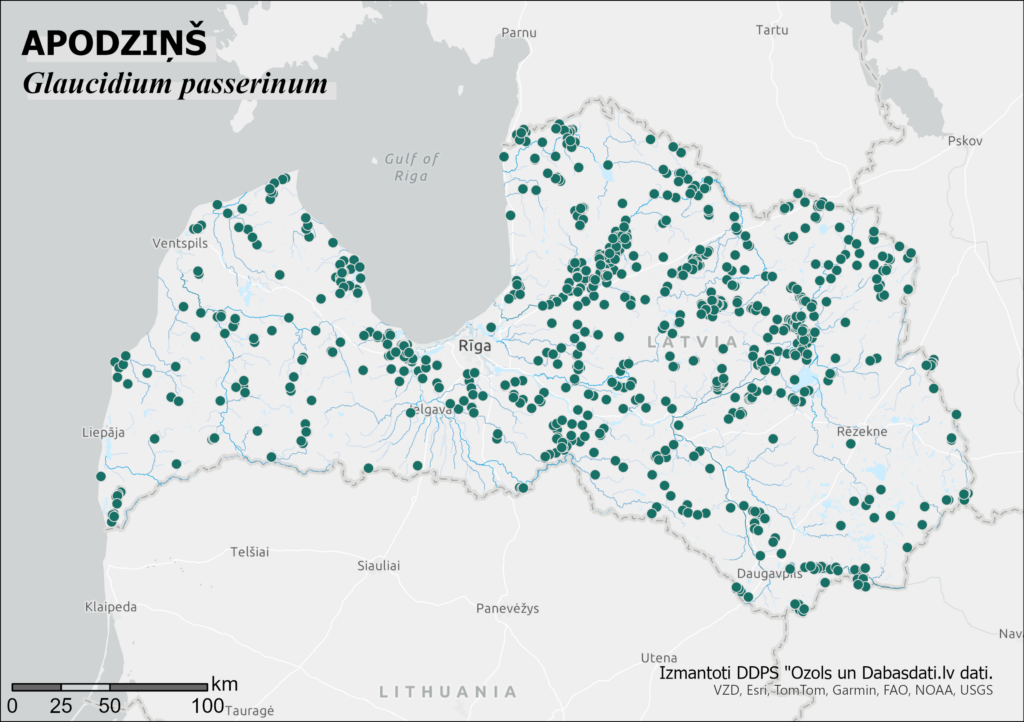

Do you know which is the smallest owl species living in Latvia and Europe? It’s this month’s protected species – the pygmy owl (Glaucidium passerinum).

A gallery of photos submitted to the "Green Treasures" photo contest features beautiful images of this tiny owl.

The pygmy owl is truly small—about the size of a starling—with a relatively small, round head. Its back is dark brown with fine pale spots, and its belly is whitish with brown vertical streaks. The facial disc is subtle and mottled. The eyes are yellow, and unlike some other owls, the pygmy owl does not have ear tufts. It has a hooked, greyish-yellow beak and proportionally large feet, which allow it to lift and hold surprisingly large prey. The legs and toes are yellowish with black claws.

This species can be identified by its distinctive calls, which vary seasonally. Both males and females can produce similar whistling sounds. Until the early 21st century, the pygmy owl was considered rare in Latvia, largely because owl surveys were typically conducted at night. However, it was discovered that pygmy owls are most active during twilight hours, when their main prey—voles—are also active. This insight led to a shift in survey methods and helped gather more accurate data on the owl’s presence in Latvia.

The greatest threat to the pygmy owl in Latvia is forestry activity, which destroys its habitat and causes disturbance. Logging during the breeding season can cause nest abandonment. A decline in rodent populations can also negatively affect breeding success. Disturbance from photography or other human activity can also pose a threat. Furthermore, climate change is expected to have a negative impact on Latvia’s pygmy owl population.

In the LIFE FOR SPECIES project, the pygmy owl is classified as a vulnerable species (VU).

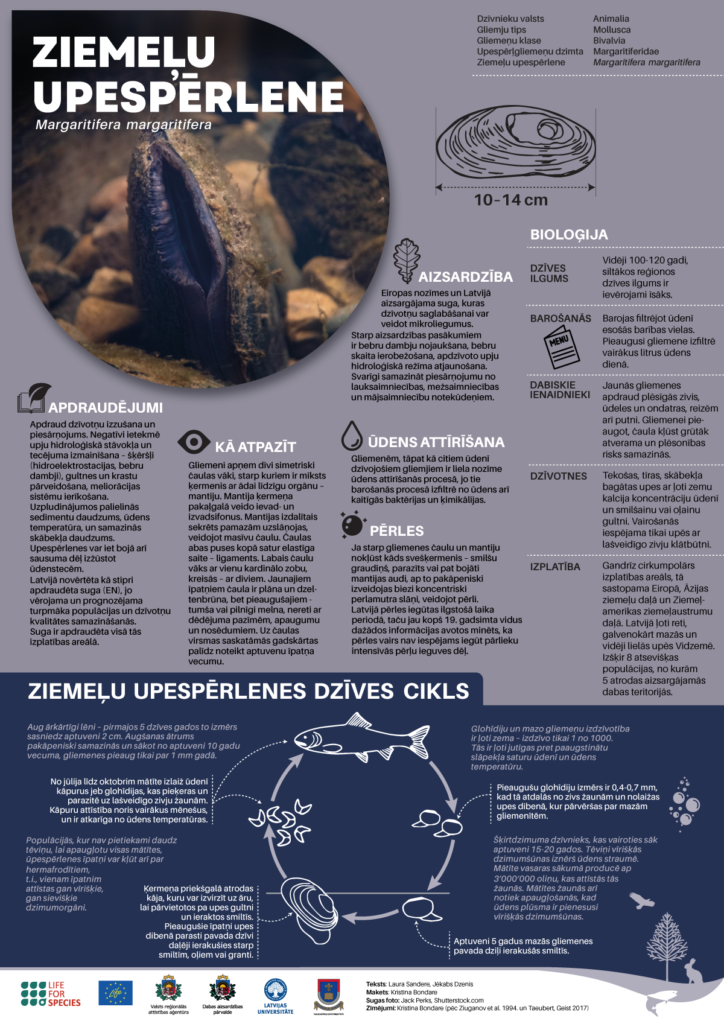

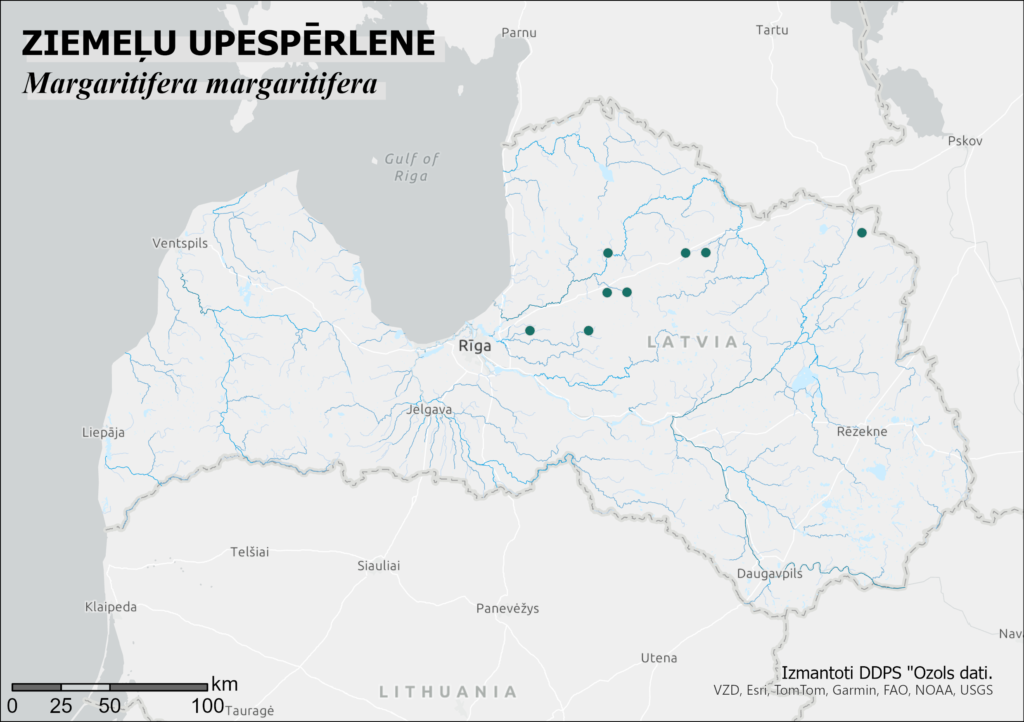

This February, we shine the spotlight on the freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera)—a species assessed in our project as Endangered (EN), facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild.

How can you recognize the species?

The mussel is enclosed by two symmetrical shell valves, which protect its soft body and a skin-like organ called the mantle. At the rear end of the body, the mantle forms the inhalant and exhalant siphons. The mantle secretes material that gradually builds up the thick shell.

The two shell halves are held together by a flexible ligament. The right valve has one cardinal tooth, while the left has two. Juvenile mussels have thin, yellow-brown shells, whereas adults have dark or completely black shells, often showing signs of wear, encrustation, or sediment deposits. The visible growth rings on the shell surface can help estimate the mussel's age.

If a foreign object—such as a grain of sand, a parasite, or damaged mantle tissue—gets trapped between the shell and the mantle, the mussel gradually covers it with thick concentric layers of nacre (mother-of-pearl), forming a pearl. In Latvia, pearls were historically harvested over a long period. However, since the mid-19th century, various sources have noted that pearls could no longer be collected due to overharvesting.

In Latvia, the species is threatened by habitat loss and water pollution. The main risk is juvenile mortality in the first few years of life, as the young are extremely sensitive to elevated nitrogen levels in the water. The species also suffers from changes in river hydrology and flow, including obstacles like hydropower plants, beaver dams, as well as riverbed and bank alterations and drainage system installations. In dammed areas, sediment levels and water temperatures rise, while oxygen levels drop. Pearl mussels can also perish during droughts when streams dry out.

On January 22, 2025, the Estonian Environmental Board hosted a conference in Tartu titled “Eesti kaitsealuste liikide nimekirjade kaasajastamine” (“Updating Estonia’s List of Protected Species”).

The aim of the conference was to introduce professionals working in Estonia’s environmental sector to the plans and actions for updating the national list of protected species, present the current situation regarding species conservation in Estonia, and more.

At the event, Dmitry Telnov, the coordinator of the invertebrate species group within the LIFE FOR SPECIES project, representing the University of Latvia’s Institute of Biology, was invited to deliver a presentation titled “Towards a New National List of Protected Species in Latvia: LIFE FOR SPECIES Project Approach.”

The Latvian LIFE FOR SPECIES project was praised during the conference for its systematic approach to preparing Latvia’s list of protected species, transparency, and criteria-based methodology. The project was also commended for its significant contributions to communication efforts related to species conservation and project activities, including seminars, exhibitions, conferences, and interviews. Participants expressed interest in Latvia’s planned and existing categories of species protection, as well as in the financial benefits associated with species conservation.

Other presenters at the conference represented the Estonian Environmental Board, the Estonian Ministry of Climate, and the University of Tartu. In total, there were eight presentations.

A significant portion of the conference was dedicated to questions from experts and other attendees directed at the Estonian Environmental Board, which is coordinating the project to update the national list of protected species (2024–2028). The project is currently in its initial phase and aims to review the status and categories of all species already included in the list. However, the list itself will remain unchanged. This means that all species currently listed as protected in Estonia will retain their status after 2028, though some may be reclassified into different categories based on their current population status. Additionally, the system of species protection categories in Estonia will not undergo changes.

The conference was attended by over 220 participants, including more than 120 in person and over 100 joining online. The attendees represented various Estonian environmental institutions, NGOs, and other organizations, including nearly all of Estonia’s environmental experts.

For more information about the conference, visit: https://www.keskkonnaamet.ee/sveitsi-eesti-koostooprogrammi-elurikkuse-programm

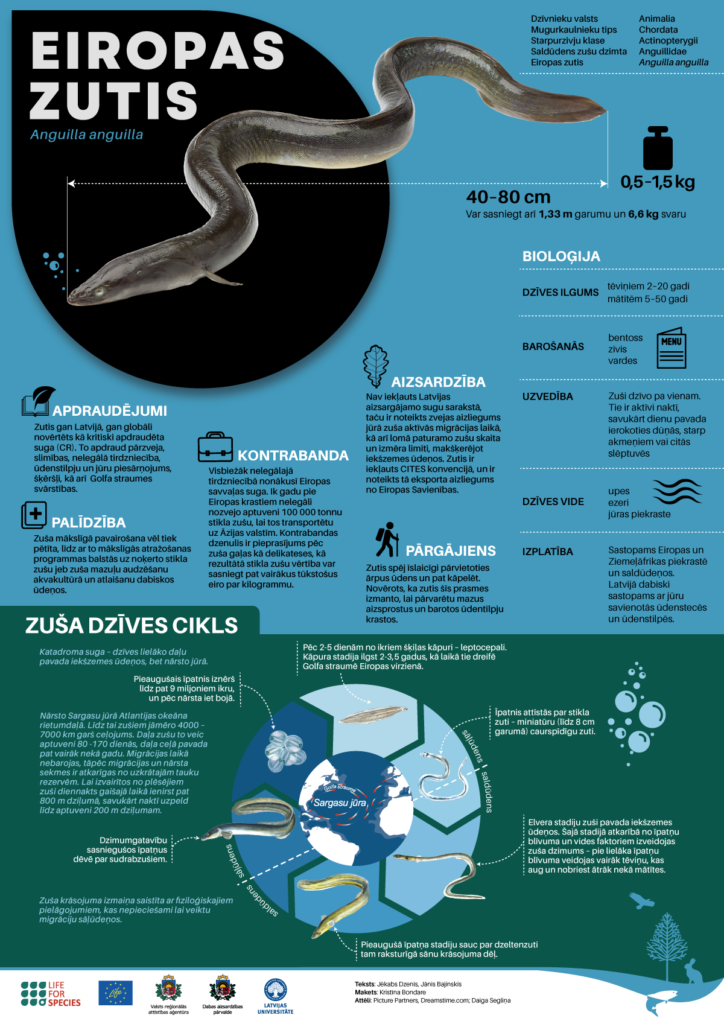

Do you know which fish can move short distances on land and even climb to overcome obstacles? This month's protected species is the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). These remarkable abilities help the eel navigate small barriers and forage along the edges of water bodies.

The European eel is classified as Critically Endangered (CR) both in Latvia and globally. It faces numerous threats, including overfishing, disease, illegal trade, pollution in rivers and seas, migration barriers, and changes in the Gulf Stream.

Unfortunately, the European eel is also the most frequently trafficked wild species in Europe. Every year, around 100 tonnes of glass eels are illegally caught along the European coast and smuggled to Asian countries. The high demand for eel meat as a delicacy drives this black market, with the price of glass eels reaching several thousand euros per kilogram.

Learn more about the European eel in the eel fact sheet. The PDF version is available here.

Fact sheet design by: Kristīna Bondare.

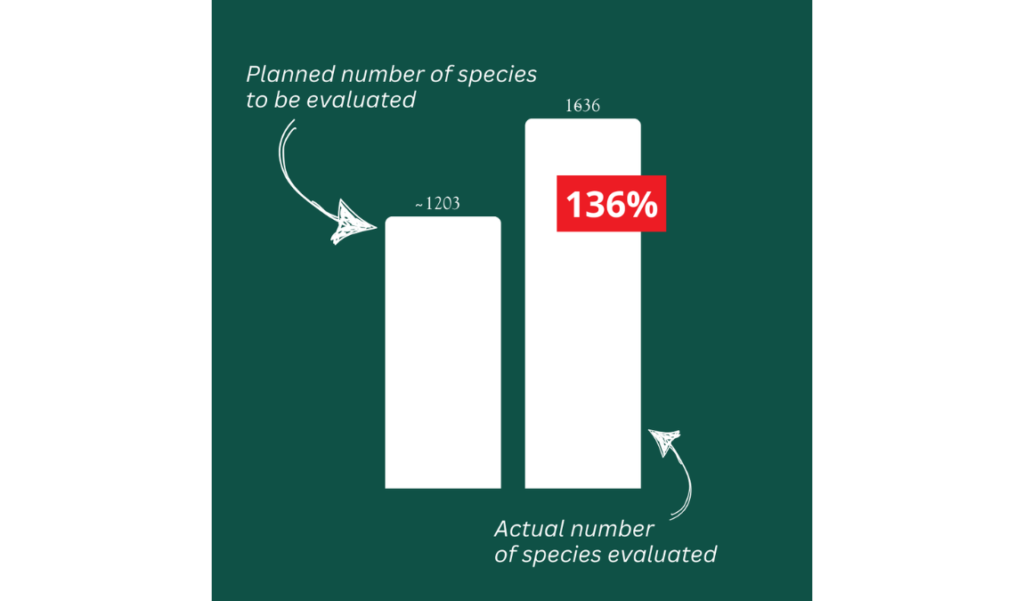

The LIFE FOR SPECIES project began on December 1, 2020, and was initially scheduled to conclude at the end of 2024. However, the project assessed one-third more species than originally planned, significantly increasing the workload. To complete all planned activities, the project has been extended until the end of 2025, and the new Red Data Book is also expected to be released this year.

While the Red Data Book is being finalized, we invite you to explore publications prepared by experts on the evaluation results of various species groups:

In 2025, we will continue to host educational events and share updates about the project through various communication channels, including our social media accounts and the project website. Later this year, we will announce details about the book launch event and the project’s closing event. Follow us on social media (Instagram, Facebook) to stay up-to-date with the latest news!

The aims of the LIFE FOR SPECIES project are to update the list of protected and endangered species based on scientific criteria, to prepare proposals for changes in legislation, to improve data quality and availability of species, as well as to increase public and stakeholder awareness, and active species protection in Latvia.